America’s Requirements

Much of America’s surveying practice descended from the English, but our early surveying equipment did not. The Old World used the delicate, expensive theodolite to divide its lands, sighting on points and measuring angles on a divided, graduated circle. American surveyors needed to establish boundaries over vast wildernesses that were difficult to traverse, and they needed to do it quickly and cheaply. Enter American innovation, technology and craftsmanship to improve a device used by mariners for hundreds of years, a form of which was being made in England: the magnetic compass. The result was the rugged, inexpensive standard American compass. One commentator said of the American compass: “Where accuracy can be sacrificed to speed and cheapness.”

The Compass

Rugged, the compass with its body of wood or brass, two sight vanes, a leveling device and placed on a staff or tripod, it required only a balanced magnetized needle resting on a sharp point. The needle aligned itself with the earth’s magnetic field and pointed to magnetic north. Magnetic north was known to move and hence was a poor direction with which to reference boundaries. This movement was well known, noted in some 1746 instructions that it “. . . may in time occasion much confusion in the Bounds . . . and, Contention.” Variation, the angle between True Meridian (a line of longitude) and Magnetic North was known to differ at different locations on earth, and the angle was known to change in amount over time and location. True North was a better reference direction, and in 1779, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the plats of surveys were to be drawn “protracted by the true meridian,” and the variation noted.

The first standard American compasses were “Plain” compasses. They used magnetic north and had no mechanism for applying the variation angle, converting magnetic direction to true direction.

David Rittenhouse (1732-1796) was an American man of science. He is generally credited with adding a vernier to the plain compass so one could “set off” the variation, the needle still pointing to magnetic north, but the bearing to the object sighted read on the compass circle being the true bearing. Thus the “plain compass” became the “vernier compass,” a great advancement in the American compass.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 specifies that all lines be surveyed “by the true meridian . . . the variation at the time of running the lines thereon noted.” Tiffin’s Instruction of 1815 (the first written instructions issued by the GLO to its Deputy Surveyors) specified “a good compass of Rittenhouse construction, have a nonius division . . .” This is a vernier compass, “nonius division” meaning a vernier. Thus, the vernier compass became the standard instrument for surveys of the USPLSS. Until . . .

William Austin Burt and his Solar Compass

William Austin Burt (1792-1858) was a GLO Deputy Surveyor who, in 1835, while laying out townships in Wisconsin, noted unusual deviations in the lines surveyed using his compass. He began work on a method and form of compass that would determine the direction of the true meridian independent of magnetic north. He invented an ingenious device that uses the observer’s latitude, the sun’s declination and local time to determine true north. The device mechanically solves the PZS (Pole Zenith Star) Triangle. The prominent Philadelphia maker, William J. Young (1800-1870), built the device, and Burt was awarded Patent 9428X on Feb. 25, 1836.

Burt made improvements to his solar compass, and an improved version was patented in 1840. In 1850, Burt’s patent expired, which allowed other makers to produce the solar compass. (The circumstances of the expired patent are a sad story.) There are about 12 known post-1850 makers of solar compasses. All the solar compasses made before 1850 are marked “Burt’s Patent” and “W.J. Young” or “Wm. J. Young,” as he made them. They are not dated or numbered. Those made by Young after about 1852 are numbered.

Is it a transit or a theodolite?

Generally, theodolite refers to an instrument with divided circles to measure both horizontal and vertical angles to high precision; the telescope is relatively long and will not transit (rotate 360 degrees) about its horizontal axis. The more common term “transit” refers to an instrument with both horizontal and vertical circles (only horizontal on early transits), a four screw leveling head, bubbles for leveling and a telescope that will transit. William J. Young is credited with building the first dividing engine in America. That allowed him to cut circles, and he is credited with building the first American transit in 1831.

The transit developed and attachments, such as a variation on Burt’s solar compass, were added by many manufacturers. For mining applications, parallel telescopes were added, thus allowing sightings at large vertical angles into steep mine shafts. Large precise transits were constructed for control surveys and astronomical observations. Horizontal circle diameters can be as large as 18 inches.

Collecting and Values

Early and vintage surveying equipment is highly collectible. It is the surveyor’s heritage, it represents about 200 years of advancing measurement technology, and some illustrate incredible craftsmanship and artistry (especially the early makers). As with other collectibles, there are highly desirable, usually rare instruments (such as the solar compass). And the early Virginia and Pennsylvania makers made compasses that are works of art. But even instruments by prolific makers like W. & L.E. Gurley and Keuffel & Esser are desirable.

There are many collectors of early American surveying equipment, some with very large collections. Most collectors buy and sell instruments, research makers and surveying equipment, and a few offer repair and restoration services. Most collectors focus on a particular maker (or two), others focus on the makers of a particular city (St. Louis, for example), and others are interested in a particular instrument form (such as transits with unusual attachments). There are online resources for early surveying equipment, such as www.surveyhistory.org, run by David Ingram. The Facebook page “Antique Surveying Instrument & Ephemera,” is run by Dale Beeks. And www.compleatsurveyor.com is run by Russ Uzes. Among the collector community, there is broad and deep knowledge of early American surveying equipment, but that knowledge is not well documented. There are not many reference books on the makers and their equipment. A few have been covered in articles and short treatises, but there are not good reference materials on the broad topic.

What are we going to do with Grandpa’s surveying stuff, and what’s it worth?

Regrettably, there is no national museum or repository where surveying equipment can be donated. Beloved equipment left to families or owned by old surveyors and seeking a home have limited options. The Smithsonian will not accept any such equipment, except for historically important equipment with known provenance. Most such equipment is not highly valuable. It is likely that 90% of such equipment would be worth less than $1,000 per piece. Eight percent would likely be worth up to $10,000. One and one half percent up to $100,000. And the last 0.5 percent over $100,000. Most collectors will have no interest in about 90% of the equipment offered to them (they already have plenty of early to mid-1900s: Gurley and K&E transits and levels). The best recipient for most low to mid-level surveying equipment may be a local museum, particularly if the equipment was used in the area by a local surveyor.

As with most collectibles, old or vintage surveying equipment is not worth what it was 10 or 20 years ago. The rare, unusual, historically important pieces have not lost their value during that time period and can easily be sold.

The Future

Boundary surveyors, being mensurators, detectives and historians have an appreciation for the equipment that laid out America. The equipment is our heritage, to be preserved, admired, studied and displayed. Every boundary surveyor needs an old compass and a chain proudly displayed on their desk.

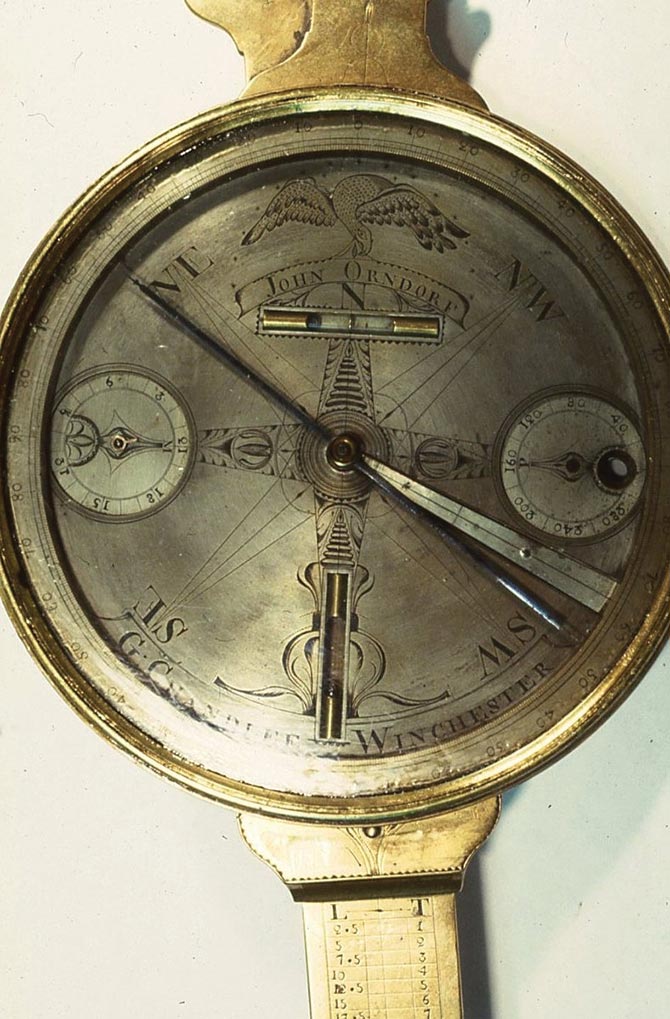

The face of a Goldsmith Chandlee (1751-1821) vernier compass; Winchester, VA, circa 1800. Eagle holding banner with “John Orndorf”

for whom the compass was made.

Solar Transit by W. & L.E. Gurley; Troy, NY.

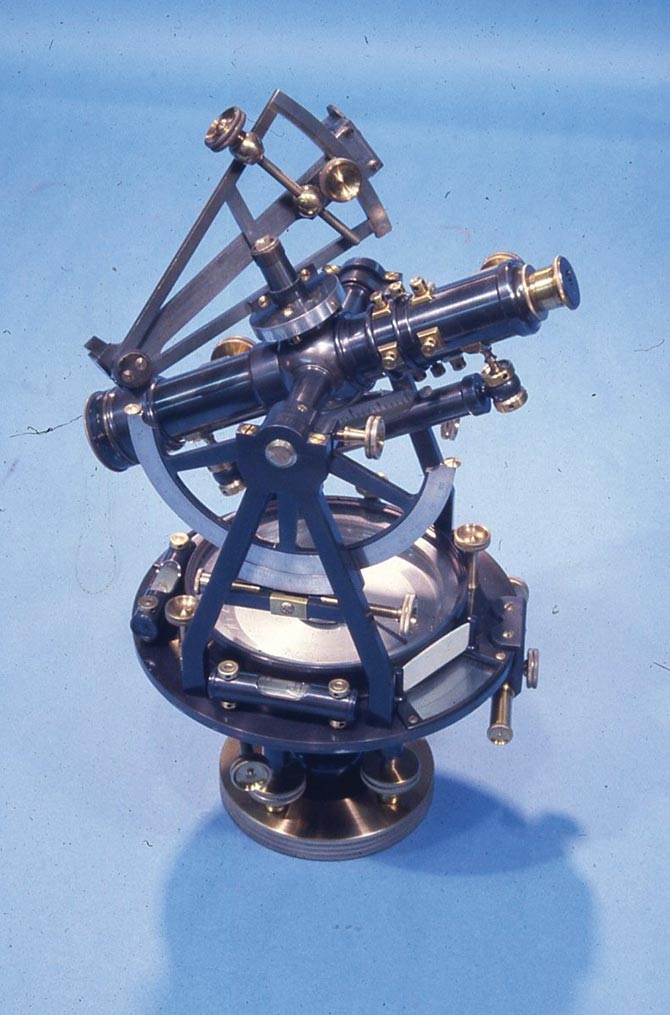

This is one of the first transits made

in America. William J. Young, Philadelphia. Three-minute least count, bullseye bubble. Was made in the very early 1830s.

The standard American vernier compass by W. & L.E. Gurley. This form with vernier, outkeeper, sights, level vials, was made from about 1860 and remained in the Gurley catalogs into the 1930s. It attached to

either a tripod or Jacobs Staff.

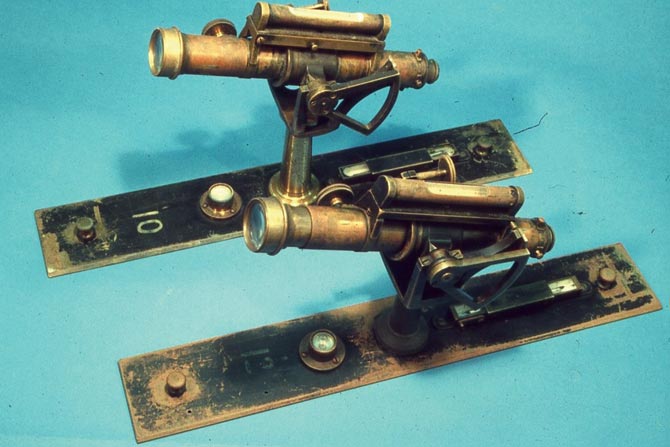

Telescopic compass (not a transit) by Blattner & Adam; St. Louis, MO. Late 1800s.

Two alidades by Fauth & Co., Washington, D.C.

A rare Solar Compass by a very rare maker, John S. Hougham; Franklin, IN. Compass was made about 1861.

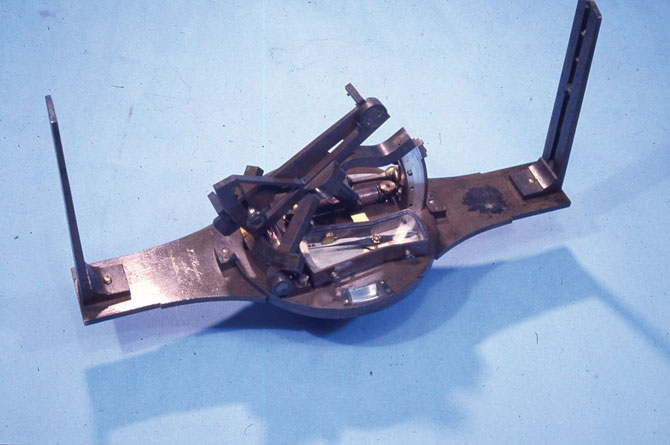

Gimbaled compass by James Reed (1792-1878)

of Pittsburgh. Used in the mines.

An assortment of chains: Gunter’s Chain,

66 feet. A half-chain, 33 feet. Railroad

or Engineer’s Chain, 100 feet.

Dr.Elgin is a surveying practitioner, educator, researcher and author. He owns a large collection of early American surveying equipment. He is an expert in the Chandlee family of makers, John S. Hougham (Indiana) and the St. Louis Makers. He’s written several books, including Riparian Boundaries for Missouri, Legal Principles of Boundary Location for Arkansas and The U.S. Public Land Survey System for Missouri. He coauthored the Sokkia (Lietz) Ephemeris. He can be reached at elgin1682@gmail.com.